Across APAC, local firms and multinationals with bases here have a long and proud record of corporate philanthropy and social engagement. In the past decade or so, there has been an increasing emphasis on the 3Ps of People, Planet and Profit, and it has been widely recognised that they can – must – work in harmony.

To provide a rounded picture, we also surveyed local consumers to find out how they feel these days about brands committed to social engagement. That was undertaken by Pollfish, who surveyed the views of 450 consumers spread across Hong Kong, Singapore, Australia, Japan and China.

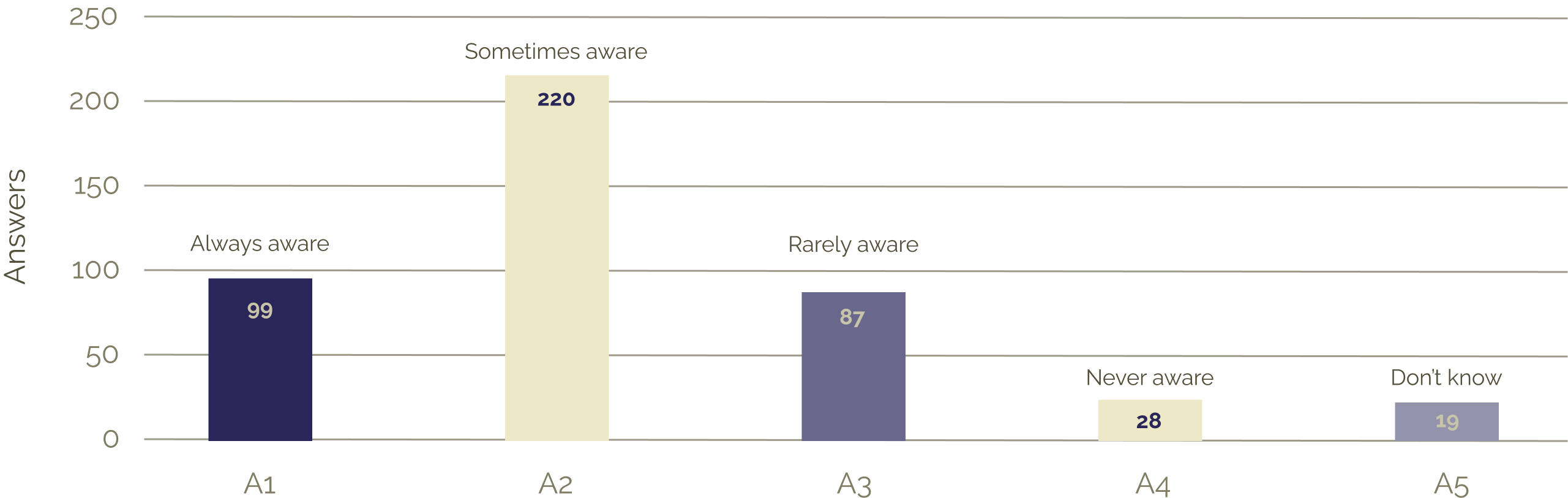

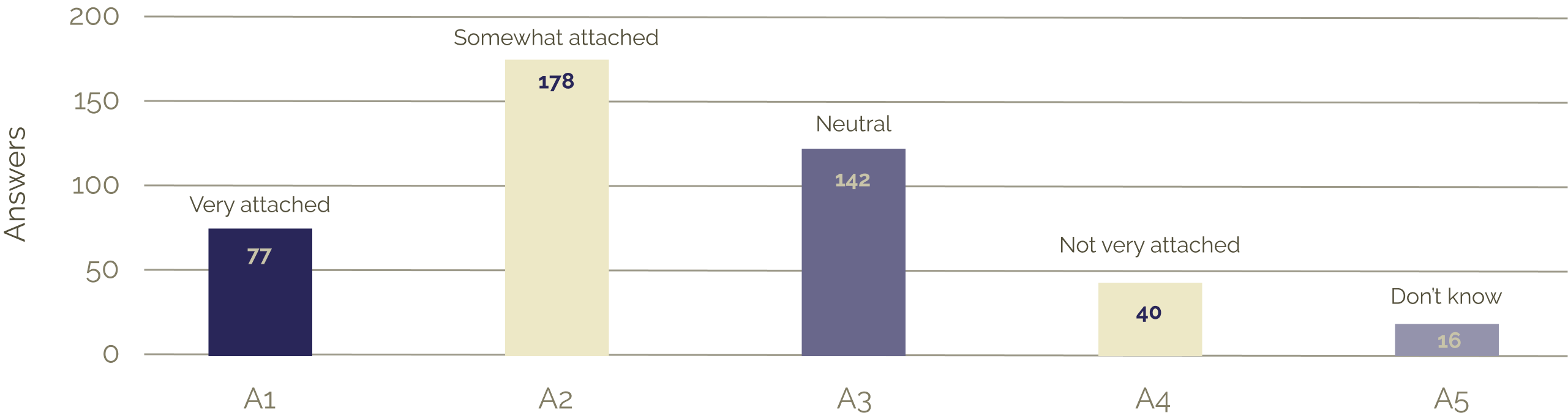

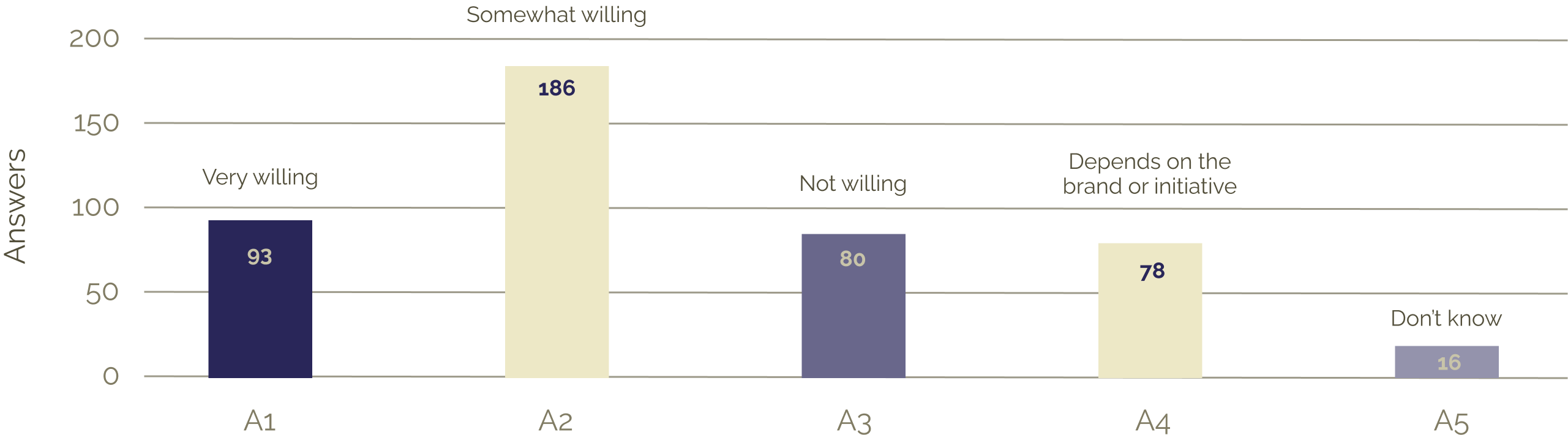

When we asked consumers across APAC whether they notice the social activities of companies they engage with, a surprisingly high proportion, almost two-thirds, told us they are sometimes or always aware of them. More than half our sample said this triggers increased loyalty to those brands, and more than a third of the total said they would even be willing to pay higher prices to support brands engaged in social activities.

For the first time, companies now started to see potential benefits to themselves from these kinds of engagements, by building positive reputations and winning various awards and kite-marks that might increase their customer base and attract a pipeline of talent.

Although it is difficult to quantify, any cursory Google search will throw up dozens of articles by the likes of Alliance Magazine, the Conference Board, the Economist, the Philanthropy Asia Alliance, and the Philanthropy Guide telling us that corporate philanthropy is rising and maturing in Asia Pacific.

Some of this has a religious dimension. For instance, Southeast Asia is home to the world’s third largest population of Muslims, with majorities in Malaysia, Brunei and of course Indonesia, where its 270m people comprise the largest number in any single country on the planet. To them, the concept of zakat, one of the Five Pillars of Islam, is fundamental, and it motivates much corporate giving.

Malaysia has prioritised corporate philanthropy as part of its current presidency of ASEAN, where Mohamed Nazir Rasak, former chairman of CIMB Group, the Malaysian financial services provider, has played a crucial role. There has even been speculation some ASEAN countries may soon adopt a 2% CSR law similar to that in India. Insiders have told us this could offset reductions in donations from the US, which in any case often has a domestic focus on highbrow artforms and elite education as much as on alleviating poverty and addressing climate change.

In China, the Common Prosperity Strategy has a corporate social dimension that has encouraged major firms including Alibaba, Tencent and other tech giants to contribute via GONGOs, Government-Organized Non-Governmental Organizations. This is part of a wider trend in the APAC region for companies to engage in social action directly rather than through arms-length corporate foundations, and thereby improving the focus on service delivery rather than simply driving donations, which have in any case risen almost 20% in the past 15 years.

Given this context, it is no wonder that in our consultations we discovered many stellar examples in Asia Pacific of social engagement activities today. We could have chosen many from those we spoke with, but we illustrate below just a few of those we found.

The index enables organisations to benchmark mental health strategies, measure impact and design programs for employees grounded in scientific evidence. For Watson, the business case behind improving employee mental health is clear. “There’s a very strong correlation to performance,” he says. “So this is a no-brainer for a CFO. This is a business metric, and if you take it seriously, it will increase your productivity because people will be in flow.”

Chair/Advisor AXA (Boards) & Liberty Mutual Group (Board).

Watson believes the purpose conversation in Asia needs to be rooted in the regional context. “It’s about continuing to move the needle,” he says. That means redefining the narrative in ways that resonate locally.

In a region where aspiration often drives behaviour, Watson sees a unique opportunity. “It’s not about putting a Ferrari on stage and saying you can win it if you’re the top salesperson,” he explains. “We need to redefine aspiration for the younger generation.” He shares the example of a Hong Kong entrepreneur who donates 25% of his profits to building hospitals: “If you can have someone like that up on stage, then suddenly the aspiration becomes: I want to be like them.”

But aspiration alone isn’t enough. Watson says many social impact initiatives fail to gain traction in Asia because they lack senior-level support. “When you have these collaborations, the CEOs don’t show up. The people who do are passionate, but without decision-making power, it’s hard to drive real change.” That’s one reason he co-founded the Shared Value Initiative in Hong Kong, promoting the idea that business success and social progress are mutually beneficial.

To help further bridge that gap between intention and implementation, Watson has also co-founded the World Flourishing Organisation, a social enterprise providing data-driven tools to track and improve employee wellbeing. Its science-based model gives leaders actionable insights that link culture to business outcomes, offering a compelling alternative to traditional engagement surveys. “CEOs aren’t going to go out of their way to drive this,” says Watson. “But if you give them a practical tool, and get some accountability from the board, that’s how we will move forward.”

Next case study: Nestlé Indochina

Nestlé’s current strategic direction – “good for you, good for the planet” – reflects the CSV philosophy. It’s a virtuous circle: by building trust and investing in sustainability, the company earns consumer preference. That, in turn, enables further investment in shared value.

Consumer expectations are a growing driver of change. “Sustainability is already firmly on the agenda,” says Seah. “In ten years, consumers will make it a license to operate.” Being a first mover helps Nestlé lock in lower costs and sharpen its messaging, he says. “If you communicate it well, you have a massive advantage.”

He points to the company’s “Crush On You” Valentine’s campaign in Thailand, which used playful messaging to promote plastic water bottle recycling. These efforts, he says, also strengthen Nestlé’s employer brand, particularly among young talent: “Many young people today are inspired by the work we’re doing. It’s a future license to recruit.”

Next case study: Nomura

“This was more than just a competition to us. It was a shared effort to make the world a little better. Thank you for creating this platform and reminding us that corporate social responsibility isn’t just a box to tick.”

Other social impact benefits for employees, such as volunteering leave and a donation-matching program, have been introduced to make participation more accessible and rewarding. Over the past financial year, employee engagement in social contribution activities in AEJ has increased by 65%.

Next case study: AstraZeneca

AstraZeneca is an excellent example of a company aligning its unique market position and intellectual know-how with a social need it was well placed to identify. In the West, lung cancer is mostly associated with older male smokers, but in East Asia, higher incidences occur among women who have never smoked—often due to cooking fumes in poorly ventilated homes. To address this, AstraZeneca partnered with an Indian startup to use AI to identify likely cases of lung cancer in underrepresented communities.

AstraZeneca’s policy change work is integral to its broader “Transform Care” strategic pillar, which aims to fundamentally change how patients experience healthcare. Mr Darroch-Thompson contrasts this with more cosmetic or siloed efforts that he sees as outdated: “These things have to be integrated within your overarching strategy and they have to make sense as part of your overall delivery.”

Because public health policy changes can take years, part of his role is helping colleagues understand its strategic value. “When you talk to people who are purely commercially focused, they’ll often be looking at this with relatively short-term financial goals in mind,” he explains. “So we try to help them see the longer view and that the right thing for the company is to build lasting, trusting relationships with governments.”

That long-term view is reflected in how goals are set. “When we sell a policy change goal, there will be an ultimate commercial outcome,” he says. “We have to convince the commercial side it’s worth going for, and once we’ve aligned, my metrics and milestones are all policy- and patient-impact based.”

For Mr Darroch-Thompson, leadership in oncology goes beyond market share: “It doesn’t mean we sell the most medicines. It should mean we’re thinking about what’s right for the oncology system, for the health systems we work with, and the patients we serve.”

Like any business, FWD needs to work within its investor commitments. With rising GDP, shifting demographics and a growing middle class in countries like Indonesia, Mr Huynh articulates the rationale: “The people that we touch in the early days who become more affluent as they go up the economic ladder are our customer base of the future. Not the distant future, the very near future.” By investing in underserved communities now, FWD is building brand trust and market share in some of the region’s fastest-growing economies.

And when those countries and customers thrive, so does the business. “For us to be successful, our community has to prosper,” says Mr Huynh. Making that connection clear from the outset to investors and the board has been critical. “The key thing for us as management is to ensure the linkage between the long-term social investment aspect versus the profitability of the company,” he adds.

It is quite clear there are world-leading examples in Asia Pacific of social engagement by businesses. It is also apparent that many others in the region have nibbled at the edges and are keen to bite off more, but are looking for guidance on how to move forward with least resistance and greatest impact. Drawing from the lessons of the one to teach the other, several relevant themes emerged in this research.

AUSTRALIA

Level 16, 175 Pitt St,

Sydney NSW 2000,

Australia

Tel: +61 0478930599

HONG KONG

18/F, Soundwill Plaza II-Midtown,

1-29 Tang Lung Street,

Causeway Bay,

Hong Kong

Tel: +852 93856861

SINGAPORE

120 Robinson Road #15-01

Singapore 068913

P. +65 8883 9910